How students can help EU policies work better thanks to open data and civic technology

Javiera Atenas - November 30, 2016 in data, featured, guestpost, oer

Post written by Luigi Reggi

Three small but important steps toward a more participatory EU policy were made in the last few weeks between Brussels and Rome, Italy. They are three episodes of a series of productive encounters between students equipped with open data and civic technology and policy makers managing EU funding.

Civic monitoring of EU funding as a way to assess results

The first episode happened in Brussels. On November 22, a group of Italian higher education students engaged in a productive discussion with the European Commission – DG Regional and Urban Policy and the EU Committee of the Regions. The debate was focused on the role of open data and public participation to assess the results of the European Cohesion Policy from the point of view of the final beneficiaries.

The team MoniTOreali – composed of students from the University of Turin and led by Alba Garavet, responsible for Turin’s Europe Direct Centre – had the chance to present the results of an intense “civic monitoring” activity focused on one of the most visible EU-funded projects in the city. Its goal is the renovation of the “Giardini Reali”, the historical gardens of Turin’s Royal Palace, one of the city’s landmarks. With a total funding of less than 2 million euros, the project is hardly one of biggest investments of EU policy in Italy. However, its central position in the urban landscape gives it the potential to shape the way citizens perceive the contribution of the European institutions to the improvement of their neighborhoods.

The goal of this monitoring was to find out how the EU money was spent and whether the project delivered the promise or not.

The Royal Gardens in Turin, Italy, funded by European Structural Funds. Photo: MoniTOreali

What MoniTOreali students found was mixed results. While the project should have been completed by 2012, actually it is still under way due to a series of administrative delays. Its implementation is also influenced by a complex social environment, as conflicting social groups have different views on the future of the gardens and this had the effect of stalling policy decisions.

To disentangle this intricate web of relations, the students interviewed experts, citizens and local public administrators. They analyzed the project’s objectives, strengths, weaknesses, history and recent developments in a civic monitoring report, which was published in the independent civic technology platform Monithon, the “Monitoring Marathon” of the European funding in Italy. The students also provided suggestions and ideas on how solve some the project’s issues.

But the most interesting aspect of this experience is that Mrs Garavet succeeded in adapting the methodology of A Scuola di OpenCoesione (ASOC) – which was originally created by the Italian Government for high school students – to a higher education course. She was able to effectively combine her experience as an activist in the Monithon Piemonte civic community with the more formal, six-step ASOC methodology, which also includes sessions on open data, data journalism, EU funding, and field research. Earlier this year, Chiara Ciociola, the ASOC project manager, actively participated in the teaching activities in Turin to promote a sort of cross-fertilization between the two communities. More information on the ASOC method and results is included in the book edited by Javiera Atenas and Leo Havemann.

The idea is that an improved version of the course’s syllabus could be adopted and used by other universities in Italy and in Europe to replicate the same practice, contextualising its application. The fact that all European Countries share the same rules when it comes to EU funding can help spread a common approach.

It turned out that EU officials loved the idea. The main conclusion of the meeting was that participation in the civic monitoring of EU policy could be a way to bridge the gap between EU institutions and the public. Moreover, the spread of these activities across the EU could also help policymakers evaluate the outcome of interventions from the point of view of the local communities. This is particularly important given that, according to recent developments, EU policies will be more and more focused on actual results in terms of real change for the final beneficiaries.

More concretely, the European Commission proposed to use its programme “REGIO P2P” to fund an exchange of civic monitoring practices between EU authorities managing the funds in different Countries.

A new way to communicate policy outputs

The second episode was a stimulating workshop organized by the EU official Tony Lockett at the European Conference on Public Communication. As Lockett describes very well in this report, open data initiatives such as the EU Portal or the DG Regional Policy open data website are probably not enough to get real impact if not combined with effective citizen participation.

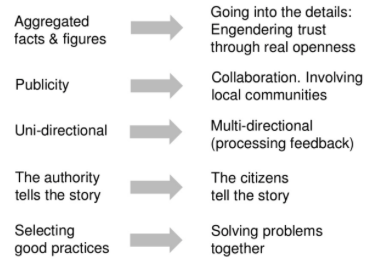

In particular, Simona De Luca – representing the OpenCoesione team at the Italian government – showed how independent civic monitoring of EU-funded projects, based on the open data published on the governmental portal, can profoundly change the way the policy is communicated to the public. While most of the “good stories” about EU funding are selected by a few experts at the managing authorities and then told by communication officers, the idea of relying on real stories by citizens for other citizens makes official communication extraordinarily powerful. People’s stories, based on official data but augmented thanks to new information collected with a sound and shared methodology, can represent not only a potential risk for the government – when the projects don’t match the expectations – but also a great way to show how problems can be solved together thanks to a meaningful collaboration between governments and citizens.

Source: OpenCoesione – The Italian open government strategy on cohesion policy

The third episode happened last week at the Italian annual meeting with the European Commission on EU Cohesion Policy. The Agency for Cohesion, a national administration responsible for monitoring the implementation of EU Cohesion policy in Italy, for the first time used the stories from the citizens to present the results of EU Structural Funds. In particular, a set of good practices from the 2007-13 period was selected based on the civic monitoring reports included in the Monithon platform. Most of the projects presented were monitored by the A Scuola di OpenCoesione high school students in different locations. The only exception was a project in Ancona, which was the focus of Action Aid’s School of participation.

Although problematic projects were not mentioned at all during the event, the presentation was the first attempt in Italy to represent the results of EU Policy “from the point of view of the citizens”. A kind of Copernican revolution for official communication that surprised most of the participants.

Current civic monitoring reports as displayed on Monithon.it

Collaborating with the Open Government ecosystem

These three examples indicate that a process of positive change is under way among European and national administrations that manage EU funds toward a more collaborative management of EU policy. However, stronger and more stable mechanisms are needed to ensure real participation in the monitoring and evaluation of EU policies.

What seems to drive this change is not only the desire for a more open and inclusive public policy, but also the urgent problem of finding out whether the projects funded really deliver or not. It is in the interest of all actors involved to assess the actual performance of the huge amount of money that flows from the EU budget to the European regions and cities, given the common ambitious goals of sustainable growth, innovation, job creation, social inclusion, and education. I believe that this question cannot be answered only with aggregated figures or econometric exercises. It requires a painstaking, bottom-up assessment of each single project involving local communities, journalists, analysts, and public officials at the EU, national and regional levels.

This is a complex task that public authorities cannot handle by themselves. They need to be ready and capable to collaborate with the whole open government ecosystem composed in this case of

- open data producers such as OpenCoesione.gov.it

- government proactive initiatives such as A Scuola di OpenCoesione, which focus on the crucial element of civic learning

- data users like the MoniTOreali group developing the right skills and expertise to provide meaningful feedback

- civic tech initiatives like Monithon

- intermediaries such as local media or NGOs aggregating and interpreting the feedback from the final beneficiaries

- policy makers willing to listen and act upon the suggestions from the public.

Monithon calls it a “monitoring marathon”, indeed.

—

If you want to know more about the open government ecosystem of the EU Cohesion Policy in Italy you can read this paper, which develops a conceptual model based on this case.

—

BIO

Luigi Reggi is a technology policy analyst at the Italian government and a PhD student in Public Administration and Policy at the State University of New York at Albany, USA. He is interested in Open Government Data, collaborative governance and European Cohesion Policy

Luigi Reggi is a technology policy analyst at the Italian government and a PhD student in Public Administration and Policy at the State University of New York at Albany, USA. He is interested in Open Government Data, collaborative governance and European Cohesion Policy

Open Education Working Group

Open Education Working Group