Today we, the OEWG, publish a joint letter initiated by Communia Association for the Public Domain that urgently requests to improve the education exception in the proposal for a Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (DSM Directive). The letter is supported by 35 organisations representing schools, libraries and non-formal education, and also individual educators and information specialists.

In September 2016 the European Commission published its proposal of a DSM Directive that included an education exception that aimed to improve the legal landscape. The technological ages created new possibilities for educational practices. We need copyright law that enables teachers to provide the best education they are capable of and that fits the needs of teachers in the 21st century. The Directive is able to improve copyright.

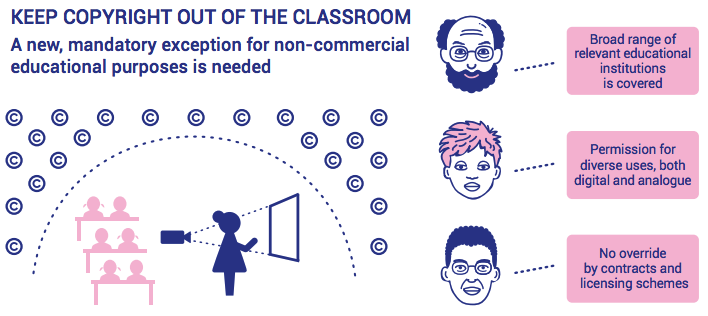

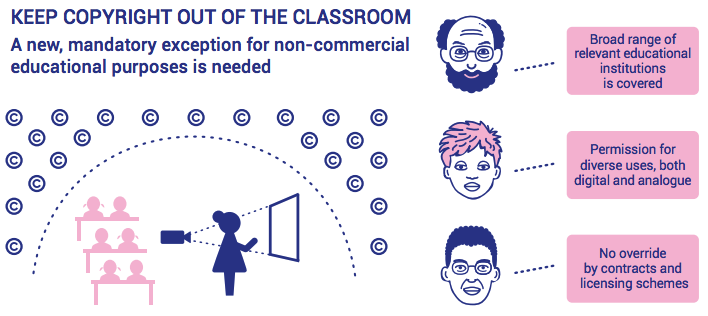

However, the proposal does not live up to the needs of education. In the letter we explain the changes needed to facilitate the use of copyrighted works in support of education. Education communities need an exception that covers all relevant providers, and which permits a diversity of educational uses of copyrighted content. We listed four main problems with the Commission’s proposal:

#1: A limited exception instead of a mandatory one

The European Commission proposed a mandatory exception, which can be overridden by licenses. As a consequence educational exception will still be different in each Member State. Moreover, educators will need a help from a lawyer to understand what they are allowed to do.

#2 Remuneration should not be mandatory

Currently most Member States have exceptions for educational purposes that are completely or largely unremunerated. Mandatory payments will change the situation of those educators (or their institutions), which will have to start paying for materials they are now using for free.

#3: Excluding experts

The European Commission’s proposal does not include all important providers of education as only formal educational establishments are covered by the exception. We note that the European lifelong-learning model underlines the value of informal and non-formal education conducted in the workplace. All these are are excluded from the education exception.

#4: Closed-door policy

The European Commission’s proposal limits digital uses to secure institutional networks and to the premises of an educational establishment. As a consequence educators will not develop and conduct educational activities in other facilities such as libraries and museums, and they will not be able to use modern means of communication, such as emails and the cloud.

To endorse the letter, send an email to education@communia-associations.org. Do you want to receive updates on the developments around copyright and education, sign up for Communia’s newsletter Copyright Untangled.

You can read the full letter below or download the PDF.

Educators ask for a better copyright

Joint Letter on the education exception in the proposal for a Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market, 16 January, 2018

Dear MEP,

We, educators, teachers, students, vocational trainers, researchers, scientists, librarians, archivists and museum professionals, provide education on a daily basis. We teach, we learn, we create and exchange information for the benefit of European society. We want a copyright framework that enables us to provide modern, innovative education. Education fit for the Europe of the 21st century. Copyright needs to be reshaped in order to facilitate modern education which spans the lives of learners, and takes place in a variety of formal and informal settings, online as well as offline.

We strongly support the European Commission’s decision to update the framework of educational exceptions and introduce a new, mandatory exception. Unfortunately, the current proposal for a Directive on Copyright in the Digital Single Market (DSM proposal) does not meet the needs of educators and educational institutions. On the contrary, it will function as a straitjacket that introduces a fragmented legal landscape and legal uncertainty. It might also mean significant, additional costs for some member states.

Instead of supporting a broad lifelong-learning sector that includes in particular adult education and workforce training – the reform will apply only a narrow range of formal establishments. Instead of supporting innovative use of digital communication to extend the mission of educational institutions, it will serve as a barrier to online education. And instead of facilitating use of a broad range of resources available to educators and learners today, it will support an outdated model that limits education to one-size-fits-all, mass-produced textbooks.

We would like to bring your attention to the following problems with the Commission’s proposal:

#1: A limited exception instead of a mandatory one

Educators should not need to be lawyers to understand what they can and cannot do. We believe in transparency. Educators would benefit from an education exception on which educators can rely across the European Union. Unfortunately, the European Commission’s proposal will maintain the fragmented legal copyright framework when it comes to education as long as licenses can overrule the exception. The consequence of the proposal is that legal uncertainty will be maintained.

#2 Remuneration should not be mandatory

Some members of the European Parliament propose mandatory remuneration for educational uses. Currently, 17 member states have exceptions for educational purposes that are completely or largely unremunerated. In these countries educators can use copyrighted works for educational purposes for free. Payments should therefore remain optional and any changes to this model should be subject to consultation with Ministries of Education of all member states.

#3: Excluding experts

Learners benefit from receiving education from the best in the field. This is why education provided by educators, librarians, museum professionals and non-formal education providers who relate to the topic of study are incredibly valuable. For instance, 24 million adults take part in non-formal training activities in libraries every year within the European Union. Unfortunately, the European Commission’s proposal does not include all important providers of education as only formal educational establishments are covered by the exception. We note that the European lifelong-learning model underlines the value of informal and non-formal education conducted in the workplace. All these are excluded from the education exception.

#4: Closed-door policy

In today’s Europe, educational activities are legitimately provided in many locations and through various means of communication. The consequence of the European Commission’s proposal to limit digital uses to secure institutional networks and to the premises of an educational establishment is that educators will not develop and conduct educational activities in other facilities such as libraries and museums, and they will not be able to use modern means of communication, such as emails and the cloud. All to the detriment of learners.

The future of education determines the future of society

We strongly urge you to avoid the above-mentioned pitfalls by granting a mandatory exception for non-commercial educational purposes that cannot be sidelined by licenses and that cannot be overridden by contract. We need an exception that includes all relevant providers of education and an exception that permits the diversity of educational uses – both digital and analogue – of copyrighted content.

We would like to stress that this is not just a concern to us, educational stakeholders, but to all citizens and society at large. Access to good education is a prerequisite for a thriving knowledge-based economy, and part of European culture. Providing access turns learners into co-creators of education, information and culture. The education exception is an investment needed to enable the advancement of science and innovation. It is an important condition not only to enable the advancement of science and innovation, but for the development of Europe and its societies.

We count on your good sense in policy and decision-making as you work to reform the copyright system in the European Union. We therefore urge all to help support access to inclusive, fair education for all in the European Union.

Sincerely,

Communia Association for the Public Domain

European University Association

Lifelong Learning Platform – European Civil Society for Education

European Digital Learning Network

SPARC Europe

Open Education Working Group, Open Knowledge International

Public Libraries 2020 (PL2020)

Expert Group on Information Law of The European Bureau of Library, Information and Documentation Associations (EBLIDA)

The International Federation of Library Associations and Institutions (IFLA)

The Libraries and Archives Copyright Alliance (LACA)

Associazione Italiana Biblioteche (AIB-WEB)

The Association of History and Civics Teachers in the Netherlands (VGN)

European Association of History Teachers (EUROCLIO)

The Slovak Chamber of Teachers (SCT)

Centrum Cyfrowe

Kennisland

ARTEdiem

Platon Schools

Alliance for Open Education

EDUin

Wikimedia Czech Republic

The Academy of Waldorf Pedagogy

Association of Teachers of English of the Czech Republic (AUACR/ATECR)

The Media and Learning Association

Neth-ER – Netherlands house for Education and Research

Association for Technology and Internet (ApTI)

The Center for Public Innovation

The Foundation for a Free Information Infrastructure (FFII)

Union of Informaticians in Education (JSI)

Mediawise Society Association in Bucharest

Centrum pro studium vysokého školství (cscš)

SOU Nové Strašecí

The Ecumenical Academy, Prague

AARTKOM s.r.o. Art of Communication

Zakladni Skola Chomutov

Elisabeth N. Fotiade, Media Literacy Educator and Chair of Mediawise Society

Milan M. Horak, priest and teacher, President of the Ecumenical Academy, Prague, Member of the Czech Christian Academy, Member of the Academy of Waldorf Pedagogy, Czech Republic

Jonathan Mason – Brighton and Sussex Medical School, United Kingdom

Mario Pena – SafeCreative, Spain

FINAL 180115 Communia – Joint Letter – Educators ask for a better copyright

Infographic available here https://www.communia-association.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Infographic_educatorsaskforabettercopyright.pdf

Open Education Working Group

Open Education Working Group

Jan L. Neumann is part of our

Jan L. Neumann is part of our

The

The