The 21st Century’s Raw Material: Using Open Data as Open Educational Resources

Javiera Atenas - March 9, 2015 in communication, data, featured

In the first of our posts for Open Education Week #openeducationwk Javiera Atenas and Leo Havemann introduce the idea of using open data as a form of OER.

In the words of the Rt Hon. Francis Maude in the Foreword to the UK Government’s 2012 Open Data White Paper [PDF], “data is the 21st century’s new raw material.” Open data is understood as “data that can be freely used, reused and redistributed by anyone – subject only, at most, to the requirement to attribute and sharealike” (Open Data Handbook, Open Knowledge, 2012).

There is a general consensus that open data is becoming an invaluable resource for the research and scientific communities, as it supports and encourages more transparent research practices, supports scientific development and reproducibility, and it can be a model of good and open research practices in academia. More and more research funding agencies and academic publishers support and even mandate data sharing. For example, papers based on research funded in whole or in part by RCUK must include, if applicable, a statement on how the underlying research materials – such as data, samples or models – can be accessed.

By R2Hox, available on Flickr CC-BY-SA 2.0

This type of data is normally shared by government agencies, academic institutions and researchers, but regular citizens and non-profit organisations also publish and release their data for other citizens to understand, for example, how money is spent, how scientific results were obtained or how cities work (see for example the work of the Open Transport Working Group). This data can be used in Higher Education to teach students using examples from real life and to help them understand the principles of data access, formats and management, as well as to assist in the development of research tools and to create new knowledge.

According to the Open Definition, “universal participation” and interoperability are key components of open data practices. We suggest that universal participation needs to be inclusive, extending the possibilities of participation beyond researchers to include students in different levels of formal and informal education. The use of open data can bring enormous benefits for students, academics and researchers in universities, as students can learn using data extracted from real research, case studies and open government data.

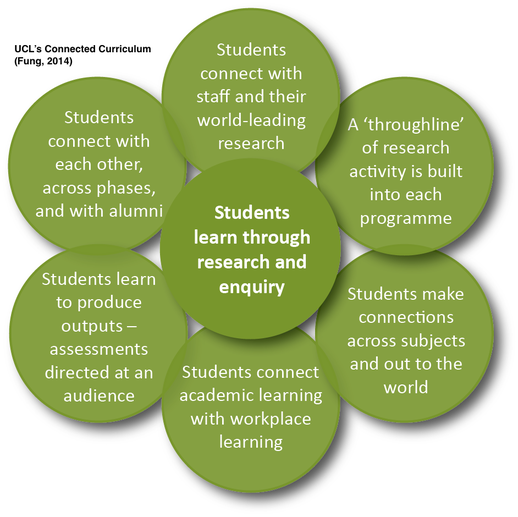

The development of critical thinking skills and the use of open data is also related with the use of open government data. Using datasets to analyse, review and evaluate the information provided by the governments, such as the data provided by the European Union, the UK’s open data portal, the UK census data or the London Data Store to mention some good examples, can help students become engaged citizens, and to use this “raw material” to contribute to society in new and yet-unimagined ways. By sharing educational resources previously kept in isolation, initiatives such as University College London’s connected curriculum scheme and other research-based learning initiatives offer insights into other possibilities for taking advantage of research data produced not only in their own institutions but worldwide.

When data is openly accessible, interoperable and reusable these type of outputs can improve the student experience as it reduces the friction between stakeholders and can potentially facilitate collaboration between academics, PhDs and postdoctoral researchers and students. Moreover, unlike educational and research outputs constrained by tighter licensing conditions and proprietary environments, open data and open educational resources allow all students to work with the same “raw materials” under the same or at least very similar circumstances. Increasing interoperability and reducing the friction to access and reuse research data should have a positive impact in research activities in universities. Research is currently lacking on open data as educational resources, and about how students can develop critical skills by using open datasets.

Researchers are sharing their datasets using open licenses in order to make them universally accessible to others, and open access repositories such as figshare support the upload and sharing of datasets and other research and educational outputs, which can then be downloaded and redistributed with creative commons licenses. However, the scientific community that embraces open science and open access remains circumscribed. The danger of the open data and open access landscape becoming an echo chamber is ever-present. Resources may be accessible, but they are not being cited, shared or reused. More to the point, in spite of different methods for open metrication, it is not yet known to what extent outputs on repositories like figshare are being used in teaching and learning. There is a need to understand how the academic community at large (beyond openness advocates) is benefiting and taking advantage of the use of open data in for teaching and learning.

By using real data from research developed at their own institution, multidisciplinary research projects enable opportunities to develop students’ research and literacy skills and critical thinking skills by establishing ways for collaborations amongst students, researchers and academics. Collaborative research work studying, analysing, visualising and reusing open data, such as the work conducted at City University London by Wood et al. visualising data from the London bicycle hire scheme (2011) and by Weyde et al. developing new tools and methods to carry out research on large-scale music collections is being used in undergraduate and postgraduate teaching, and students in these courses are increasingly aware of specific open datasets and large open data collections as research resources. For more details see the Digital Music Lab and the following paper on Big Data for Musicology.

There has also been considerable work done to create awareness of good practices in data citation (see for example DataCite, Force11 and DCC, as well some university library resources), which emphasise the role of datasets as a contribution to scholarship, as research references and as citeable outputs. However, most of this guidance is generally aimed at or known by a relatively limited number of developers, publishers of data and researchers, and not necessarily students (this may vary significantly from field to field and institution to institution, but published research and factual evidence is still lacking in this regard). Up to now it is not easy to locate dedicated studies, educational guidelines or toolkits, from the point of view of Open Educational Resources that consistently support the use of open data in teaching and learning. There is a lack of documentation and resources about best practices and standards for open data use within universities on their teaching and learning activities, and we suggest this is an area that requires urgent development.

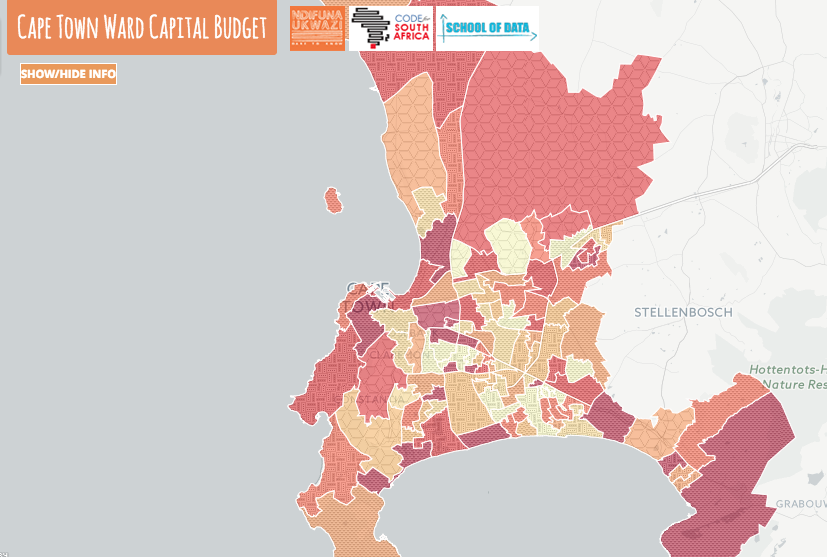

How can we, scholars, researchers and learning technologists understand and share expertise about the value of open data in teaching and learning, and about how it is being used by others? Initiatives like the School of Data (with a focus on developing data research skills in mid and low-income countries) and P2PU (with a focus on online peer learning) offer good models of what an OER-oriented open data research educational platform could look like, if resources were allocated to it.

Cape Town Budget from School of Data

Students are usually given research outputs to learn about their subjects, but these have traditionally been journal articles and books, perhaps videos and eBooks when the resources exist and licensing and access are not an issue. In many disciplines, anecdotal evidence from teachers shows that students don’t often see research datasets or the research/lab logs. We suggest these are fundamental tools to comprehend research work, workflow and processes. Students should be given the opportunity to work in groups analysing datasets to conduct discoveries of their own and/or to attempt the replication of research findings. If students are only seeing research results, they have to trust them without having the tools to question or assess the source data directly. We believe that enabling students to understand good practices in data management and to locate, collect, cite and reuse open data resources is a key research skill, and one of the ways in which teachers can ‘flip the classroom’ to facilitate independent research, teamwork and critical digital and data analysis skills.

How are academics, teachers, researchers and students working with “the 21st century’s new raw material“? We aim to understand how academics are using open data as open educational resources. Some general questions stand out:

- How academics are embracing open educational practices?

- Are academics embedding open data in their curriculum and if so, how?

- How are students in Higher Education benefiting from open data?

- How are students collaborating, learning and developing quantitative and qualitative research skills by using open data in the classroom?

As an initial stage, we have prepared a very short and basic three-question survey. If you currently use open data for teaching, could you share your experience with us? It won’t take you more than 5 minutes. You can complete the survey here. Thank you!

About the authors

Javiera Atenas is a learning technologist at University College London and holds a PhD in education. Leo Havemann is a learning technologist at Birkbeck, University of London and holds an MA in Media and Cultural Studies. E. Priego is a lecturer at City University London and holds a PhD in Information Studies.

Open Education Working Group

Open Education Working Group